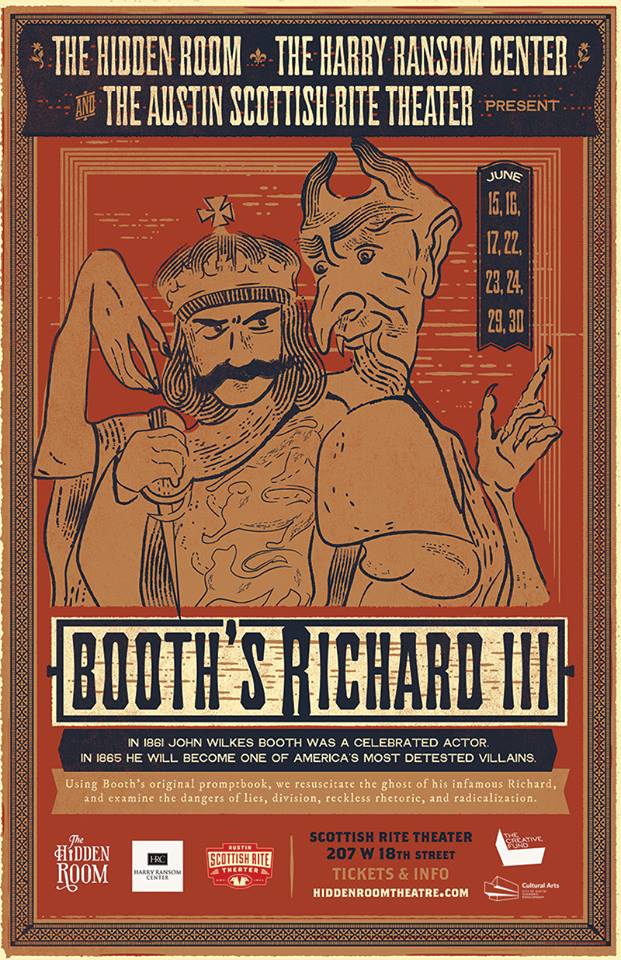

Review: John Wilkes Booth's RICHARD III by Hidden Room Theatre

by David Glen Robinson

Booth’s Richard III is Colley Cibber’s Richard III with actor/director/theatrical impresario John Wilkes Booth’s inflections. Yes, John Wilkes Booth. His radicalizing take on Richard III was found in his director’s prompt book for the play, unearthed in the massive geological literary deposits of the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin. The excavator was curator Eric Colleary, who recognized the significance of the find and communicated it to Beth Burns, Producing Artistic Director of The Hidden Room. The rest is Austin theatrical gold.

The story is Shakespeare’s Richard III, a key history play and also a tragedy. The ambitious and profoundly evil Richard III, the last of York, usurps the English throne by killing Henry VI, Henry's rightful successors, and additional family members. They were Richard’s cousins, uncles, and nephews. His forceful aggression built more and more opposition, and eventually Richard wa removed from the throne in tumultuous battle.

.jpg)

This is the meat of The Hidden Room, the company that has brought to the stage several alternative takes on Shakespeare. Director Burns has gathered close around her a company of like-minded theatre artists who polish obscure gems and set them to shine on stage. Burns applies authentic practice to the process of mounting archival works. The company researches and learns period stagecraft, music, stage management, stage choreography, fighting and weaponry, and all the design fields, particularly costuming -- right down to stylized gestures (note: actors’ toolbox equipment of the day, which has changed a lot through time, along with audiences’ tastes).

Authentic practice amounts to a deep dive into theatre history, achieved by the literary detective work of piecing together manuscripts in jigsaw puzzle fashion. It's a sort of text archeology, although when it involves Shakespeare, such Elizabethan ethnohistory is closer to an anthropological perspective on the process. In the case of Booth’s Richard III, make that Stuart (1707-1714) and Hanoverian (1704-1901) ethnohistory as well. Director Burns tells us that Booth’s Richard III was three years in development. The rewards go to the audience that attends this rare gem of theatre. Gratitude to The Hidden Room for the sharing of its scholarly art.

Richard, Duke of Gloucester, is played by Judd Farris, who clearly enjoys himself as a stereotypical archvillain. In her curtain speech Burns strongly encouraged booing the villains and cheering the heroes. The audience accepts the invitation enthusiastically, and Farris plays to it at every opportunity. His athletic build and long legs keep his distorted postures and limp throughout the strenuous battle scenes. He leaps and cavorts like some monstrous spider -- certainly a creature you definitely wouldn’t want to encounter in the Tower of London. The villanous Richard is the only character who takes the liberty to make asides to the audience. This clearly marks him in Booth’s production as the protagonist. One has the eerie feeling in 20-20 hindsight that Booth was advocating Richard’s perspective on good and evil.

_jg.jpg)

Robert Matney is the chameleon master of stylized movement, but none of it impedes his application of nuanced, often subtle, facial expressions. His crystal-clear delivery supports all of his character explorations. Buckingham is a critical pivotal character, and Matney’s character responsibilities are huge. He meets them easily and well.

Brock England offers strongly distinctive characters both as the infirm, imprisoned King Henry VI and as Richard's eventual nemesis the Earl of Richmond, distinctions assisted by the spectacular period costumes of Master of Costume Jenny McNee. England’s movement and gestures were especially supportive of the emotional tonality of his scenes. England is a committed actor of the whole being, not from the neck up.

The entire cast works harmoniously on stage, essential in a complex play such as this one, anything but naturalistic and straightforward. Cast standouots were several, and they must include Zac Crofford, Andreá Smith, Jill Swanson, Robert Deike, and Sean Christopher.

The program lists no Master of Set Design because the production takes full advantage of the brilliant antique painted backdrops of Austin's Scottish Rite Theater. Built in 1871, the venue has with a generous fly system. Famed scenic painter Thomas Moses painted the drops in 1875. They are Austin art treasures seldom seen except in the productions, many for children, of the resident Scottish Rite company headed by Susan Gayle Todd. Booth’s Richard III showed many of them though not all, with scenes ranging from coronation halls and castle holds to various deep forests, ruined chapels, abstracted dawns and fallen columns—the list goes on. The Hidden Room sometimes dropped the painted scenes into multiple planes across the stage; with these and frequent use of forced perspective, the artifice gives the already generous proscenium stage immense depth as well as imaginative geographic range.

Booth’s prompt book is based on Cibber’s 1699 rewrite of Shakespeare’s Richard III, and it reflects much of Booth’s increasingly radicalization. Director Burns cautions that the work has far less Shakespeare than of 1860s melodrama providing star turns for John Wilkes Booth. Booth himself often played Richard, with his last performance in 1864.

Booth’s prompt book is based on Cibber’s 1699 rewrite of Shakespeare’s Richard III, and it reflects much of Booth’s increasingly radicalization. Director Burns cautions that the work has far less Shakespeare than of 1860s melodrama providing star turns for John Wilkes Booth. Booth himself often played Richard, with his last performance in 1864.

So, what of Shakespeare comes through these filters, first of Cibber, then of Booth? Foremost is Richard’s self-defense of his evil deeds, bad behavior in part in response to his offputting physical deformities, about which he was quite insecure. History -- well, Wikipedia summaries -- record him as having one shoulder higher than the other. Shakespeare exaggerated that condition by adding a humped back and the limp. Shakespeare’s words out of Richard’s mouth are defensive, of the “if they will not love me I will make them fear me” variety. Shakespeare was not alone among Elizabethan playwrights to reveal the core of pain in his major characters, both positive and negative. That's one reason for our enduring fascination with Shakespeare and Elizabethan drama.

At the end of the play, the audience, fully wrought, misbehaves to the extent of cheering the final stabbing of the villain. Shakespeare cries out through time that his work is nothing if not respect for all human life, and rowdy, well-entertained audiences cannot, in all humanity, forget or ignore for a second that supreme value. This is so even though some of the play’s characters failed in their missions in life. The cautionary moral tale of Richard III appears glossed over or forgotten in Booth’s Richard III. One wonders if this influenced Booth’s radicalization or was evidence of radicalization already accomplished. Either way, on a grander scale Booth’s play conveys its ugly message that murder is justifiable in striving for ambition and power. That theme moves in parallel with the social media pages of the mass killers who struck Parkland and Santa Fe in our digital barbaric era and with the Columbine killers before them. And too many more

At the end of the play, the audience, fully wrought, misbehaves to the extent of cheering the final stabbing of the villain. Shakespeare cries out through time that his work is nothing if not respect for all human life, and rowdy, well-entertained audiences cannot, in all humanity, forget or ignore for a second that supreme value. This is so even though some of the play’s characters failed in their missions in life. The cautionary moral tale of Richard III appears glossed over or forgotten in Booth’s Richard III. One wonders if this influenced Booth’s radicalization or was evidence of radicalization already accomplished. Either way, on a grander scale Booth’s play conveys its ugly message that murder is justifiable in striving for ambition and power. That theme moves in parallel with the social media pages of the mass killers who struck Parkland and Santa Fe in our digital barbaric era and with the Columbine killers before them. And too many more

Booth famously shouted sic semper tyrannus, “Thus always to tyrants,” after he shot Lincoln and leapt to the stage. He died in a burning barn twelve days later. One wonders if his last thought might have been the last line of the play: “Let darkness be the burier of the dead.”

Booth’s Richard III by The Hidden Room runs June 17-30, 2018 at Austin’s Scottish Rite Theater. It is recommended for anyone with the even the slightest interest in theatre.

EXTRA

Click to view the Hidden Room program for Booth's Richard III

John Wilkes Booth's RICHARD III

by William Shakespeare

Hidden Room Theatre

June 15 - June 30, 2018

Tickets $15 - $30 plus service fees, available on-line HERE

Parking available in a lot behind the theatre or metered street parking

Theatre is wheelchair accessible

Find your public transit route to the theatre here: https://www.capmetro.org

[poster design by JennyMarie Jemison, Five and Four]