Review: The Beautiful People by Steven Wilson

by Michael Meigs

Don't let this gem flicker past you. Saroyan's gentle, quizzical one-act from 1941 isn't well known, and you're not likely to get the opportunity to enjoy it ever again. MFA candidate in directing Steven Wilson has magicked forth this evening with some powerful help, and it's a revelation of theatre and acting craft nestled within a revival.

You'll see nothing like it anytime soon. In Austin terms it's as if Norman Blumensaadt's devoted exploration of twentieth century classic writing has been blended with acting talents often seen at the Zach Theatre. With a bit of marketing the Zach Theatre could put this staging into its Whisenhut theatre in the round and run it profitably for a month, without a single change.

Admission is free. It is, after all, Wilson's thesis project, with technical collaboration by University of Texas students including third-year MFA graduate students William Anderson (set design) and Hope Bennett (costume design). The single-page program leaflet lists everyone in democratic alphabetical order in dizzyingly tiny print, including leading Austin actors Janelle Buchanan (an Actor's Equity artist), David R. Jarrott and Rommel Sulit. On opening night UT prof, playwright and Zach collaborator Steven Dietz occupied one of the 40 seats in the audience; Zach star Barbara Chisholm was in another.

With the constraints of academic endeavor and financing by Kickstarter, his edition of The Beautiful People is designed to disappear after only six performances before a maximum audience of about 240 persons.

Wilson and friends are staging it in grandiloquently titled Museum of Human Achievement, a lofty title for a ramshackle space behind what used to be the Goodwill warehouse on Springdale Road and just south of what used to be the Blue Theatre. Easiest access is via a relatively obscure gate on Lyons Rd. just west of the railroad tracks. Your vehicle noses into a rutted, muddy parking area. Austin's recent rains had left such large expanses of standing water that the company e-mailed ticket holders the day before to warn them to wear rubber boots or similar footwear and even offered to reschedule their seats if desired.

The gallery, bar and playing area for The Beautiful People snugly withstood the earlier wind and wrack. Designer William Anderson, a 15-year veteran of the Chicago theatre scene, has created an airy, spacious and welcoming space for the Webster house One enters via the steps that will later be used for most entrances and exits, and in each corner of the wide square space are situated two short rows of theatre seats. An upright piano awaits along one wall; a rocking chair sits next to a fireplace; a desk occupies another wall. The central space is anchored by a large rug, and panels overhead suggest the slope of the roof and tidy period wallpaper that continues in our imagination around the space.

Miscellaneous singer-songwriter music accompanies our wait for the action to begin.

Saroyan's piece depicts, very gradually, a small, eccentric motherless family somewhere 3333 miles from New York City (Saroyan often situated his fictions in Fresno, California). Thin, knobby-kneed Caleb Britton pantomimes Owen, the youngest child, in a lengthy opening sequence. We initially read him as quiet and dreamy, but with the appearance at the door of an 'old lady' (Owen's later comment) named Harmony Blueblossom (Janelle Buchanan), we soon discover that Owen is exceptionally bright and opinionated.

Saroyan uses Harmony's patient questioning to elicit from Owen an extensive exposition: his father Jonah stands on street corners to engage and lecture passersby; his sister Agnes is adored by the troops of mice ("not rats!") inhabiting the house, who deposit flowers in her honor; his brother went to New York nine months earlier and they've had no word of him for the last month. All these oddities are delivered by Owen as if in a convulsive lecture and offer a static and strange picture. The unexplained Harmony Blueblossom sits through them, waiting for father Jonah's return, but eventually excuses herself and departs. We in the audience are left with the uneasy feeling that Saroyan has boxed us into his own overly quirky writer's concept.

The playwright confounds us quickly, however, throwing first sister Agnes (the earnest Mackenzie Dunn) into that odd pond to dispute with Owen and recount her own day, and following up with their father Jonah Webster (David R. Jarrot), a reassuring patriarch garbed in high-waisted 1940s trousers with sententious and carefully noncommittal replies to his children's concerns. With his broadcaster's voice and kindly air, Jarrot has something of Walter Cronkite before Walter Cronkite was known. One of the mice has gone missing, we hear, and may have absconded to the Catholic church nearby; the inhibited Agnes has met a young man at the library; a tidily dressed young man with spectacles appears at the door with some sort of errand, but Jonah waves him away. In that role as the aptly named William Prim, David Radamés Toro retreats, abashed, but he will be back with bad news eventually.

The playwright confounds us quickly, however, throwing first sister Agnes (the earnest Mackenzie Dunn) into that odd pond to dispute with Owen and recount her own day, and following up with their father Jonah Webster (David R. Jarrot), a reassuring patriarch garbed in high-waisted 1940s trousers with sententious and carefully noncommittal replies to his children's concerns. With his broadcaster's voice and kindly air, Jarrot has something of Walter Cronkite before Walter Cronkite was known. One of the mice has gone missing, we hear, and may have absconded to the Catholic church nearby; the inhibited Agnes has met a young man at the library; a tidily dressed young man with spectacles appears at the door with some sort of errand, but Jonah waves him away. In that role as the aptly named William Prim, David Radamés Toro retreats, abashed, but he will be back with bad news eventually.

The Beautiful People shares elements with Kaufmann and Hart's You Can't Take It with You, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for drama just four years earlier -- a piece regularly revived, including a notable staging by Trinity Street Players in April 2010 and a version by Different Stages in November, 2012 with artistic director Blumensaadt in the role of patriarch Grandpa Sycamore. Saroyan's Websters are also an oddball family, not really part of the wider community, held together by a patriarch of mild authority and contrarian views, living from an income that's somewhat irregular.

But these aren't the Sycamores simply transported 3333 miles westward. With the return of Prim, the appearance of Jonah's drinking buddy Dan Hillboy (Rommel Sulit) and the visit of the local Catholic vicar (Dotun Ayobade), Saroyan's people reveal circumstances darker and unhappier than the carefree creations of Kaufmann and Hart. For all his acceptance and apparently phlegmatic attitude, Jonah Webster's an afflicted man. One son may have disappeared in New York, his daughter is in emotional distress and his youngest son is perhaps too bright for his own good (he has written several books, each consisting of a single word). Others in the play also hover between acceptance and despair. Saroyan salves some of this unhappiness; Prim, for example, is inspired by Jonah Webster's dogged even temper, and Agnes re-encounters the young man who was so awkwardly kind to her.

The playwright leaves other strands deliberately hanging, including the outcome of the older son's struggles in New York. Harmony Blueblossom turns up for the happy ending, which isn't so very happy and isn't clearly an ending at all, certainly not for her, since we never learn her identity (mother? former lover? would-be fairy godmother?). Life continues, and it requires genteel tolerance, a stoic acceptance, concern for family, and the appreciation of differences and of pains.

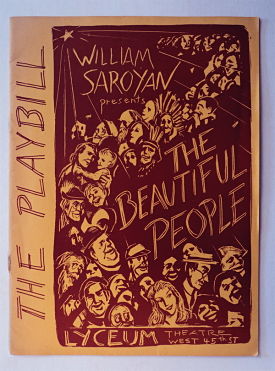

The Beautiful People that premiered in 1941 was dismissed with a sniff by Time Magazine. Other reviewers enjoyed its humor and whimsey. Brooks Atkinson of the New York Times, who had spent some time the previous day in Saroyan's company, embraced it, apparently more out of sympathy for Saroyan the raconteur than Saroyan the dramatist (". . . all his characters represent either himself or his relatives, whom he enjoys the more the thinks about them, and besides, he has a generous sense of humor. It is not wit; it is humor that comes from the differences in his gypsy philosophy and the conventional ways of the world").

None of the excerpts from reviews reprinted by Samuel French, Inc., in the playbook suggest any perception of unhappiness or pain; perhaps the Broadway staging that ran for 120 performances neatly minimized those elements or glossed them over. Director Steven Wilson has elicited a deeper sense from the story, one that's perhaps more in keeping with our modern sensibilities. As Atkinson comments, Saroyan is no Pinero, no devotee of the 'well-made play'; and in our jagged world, that's fine with us.

And although the staging is emphatically set in the 1940's, subtle modifications suggest that Saroyan's fundamental values endure. That costume for sister Agnes, for example; shouldn't she be wearing a plaid or solid woolen skirt of knee length, instead of the short flat-pleated skirt of a cheerleader from later in the century? Wilson's Father Hogan of the local Catholic church is played by tall, quiet -- sometimes too quiet -- Dotun Ayobade from Nigeria, a Ph.D. student in Performance as Public Practice. In a world now more fully visible to American audiences via the media, and with a Catholic church that in Europe is increasingly recruiting African clergy to fill vacant rectories, it's entirely appropriate that as protagonist Jonah Webster kneels at the table and speaks of his pain, the comforting hand extended to him is not that of a conventional Irish-American priest with a brogue and a twinkle in his eye.

EXTRA

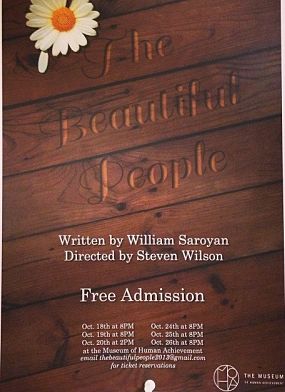

Click to view program leaflet for The Beautiful People, directed by Steven Wilson

Hits as of 2015 03 01: 619

The Beautiful People

by William Saroyan

Steven Wilson