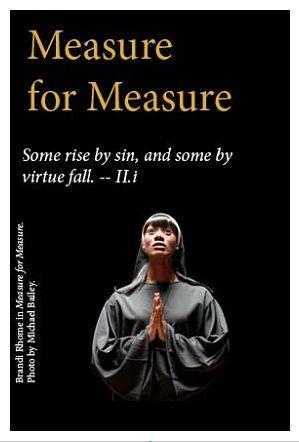

Review: Measure for Measure by American Shakespeare Center touring company

by Michael Meigs

The towering American colonial revivalist preacher Jonathan Edwards is remembered today principally for the hair-raising imagery in his 1741 sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, including especially his fierce warning,

The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked: his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; . . . you are ten thousand times more abominable in his eyes, than the most hateful venomous serpent is in ours.

Edwards was preaching 140 years after Shakespeare wrote Measure for Measure and he was addressing an entirely different community. London under Elizabeth I was Anglican, apprehensive about the enmity of Spain and the Roman church, and the theatre-going public was a rowdy, worldly, vice-ridden lot. Even so, Christian religion, moral codes and the threat of eternal damnation -- that fiery pit of hell -- were vivid in the imagination and beliefs of both times.

In Measure for Measure, the first of his works that would later be categorized as "problem plays," Shakespeare entertained with a game of disguises but examined with great seriousness issues including misrule, negligence,moral and immoral conduct, punishment and forgivenness, religious authority and secular authority, chastity, libertinism and promiscuity.

In contrast, the brave young touring company of the American Shakespeare Center plays Measure for Measure mostly as a lark. Director Jim Warren emphasizes comic elements and leaves little time for thought, even in the most challenging and perplexed of the characters' speeches. This scanting of the moral dilemmas may be related to the fact that the touring troupe frequently plays before college-age audiences, thoroughly secular young persons flush in the exhilaration of choice and freedom.

In contrast, the brave young touring company of the American Shakespeare Center plays Measure for Measure mostly as a lark. Director Jim Warren emphasizes comic elements and leaves little time for thought, even in the most challenging and perplexed of the characters' speeches. This scanting of the moral dilemmas may be related to the fact that the touring troupe frequently plays before college-age audiences, thoroughly secular young persons flush in the exhilaration of choice and freedom.

A summary may illustrate the tough-mindedness of Shakespeare's text. Duke of Vienna Vincentio opens the play with an abrupt and unexplained decision to absent himself for an undetermined period, conveying full powers to his deputy Angelo. Vicentio leaves behind a city that has long lapsed into license and libertinism, for the ruler has not applied existing stern laws against bawdry and unchastity. In fact, according to the carelessly cheerful testimony of "fantastical gentleman" Lucio and a company of lowlifes, we might call Vienna the Las Vegas of the time, if we mean the hardcore Las Vegas of gangster times, before it was turned into a mall and middle-class pleasure park.

A summary may illustrate the tough-mindedness of Shakespeare's text. Duke of Vienna Vincentio opens the play with an abrupt and unexplained decision to absent himself for an undetermined period, conveying full powers to his deputy Angelo. Vicentio leaves behind a city that has long lapsed into license and libertinism, for the ruler has not applied existing stern laws against bawdry and unchastity. In fact, according to the carelessly cheerful testimony of "fantastical gentleman" Lucio and a company of lowlifes, we might call Vienna the Las Vegas of the time, if we mean the hardcore Las Vegas of gangster times, before it was turned into a mall and middle-class pleasure park.

New governor Angelo strikes, and he strikes hard, although the only case we examine in detail is that of nobleman Claudio who has gotten his beloved Juliet pregnant without the sanction of marriage vows. Angelo decrees that Claudio must die, and he insists with a rigidity and single-minded ferocity worthy of Calvin in Geneva, less than fifty years earlier. Fantastical Lucio is dismayed at what he sees as an arbitrary and unfeeling exercise of power, so he persuades Claudio's sister Isabella, a novice at the convent, to plead with the governor for mercy.

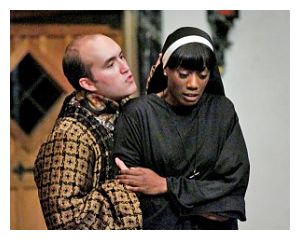

Immovable force meets irresistible object, inverting the common phrase. Moved by his own arrogant righteousness, Angelo wishes to enforce the law but he finds the purity and youth of Isabella irresistible. He struggles but finds himself consumed with the same lascivious passion for which he is punishing other citizens who have far less responsibility than he does. Angelo propositions Isabella -- if she delivers her body to him, her brother can go free. Talk about a conflict! (And they do.)

Shakespeare puts absolutes in direct confrontation. For example, Isabella tells her brother the prisoner Claudio that she scorns the "devil" Angelo and will not abandon her holy vow of chastity; Claudio, with the grave gaping before him, wants to praise her but ends up pleading for his life.

Hard straight edges contrast with hazy gray smudges. How can individuals of fallible flesh and blood achieve purity of moral virtue and yet remain human? Does virtue require absolute justice? How can one reconcile the ambiguities and contradictions of life with the terrifying prospect of God holding one's soul over that burning pit of hell?

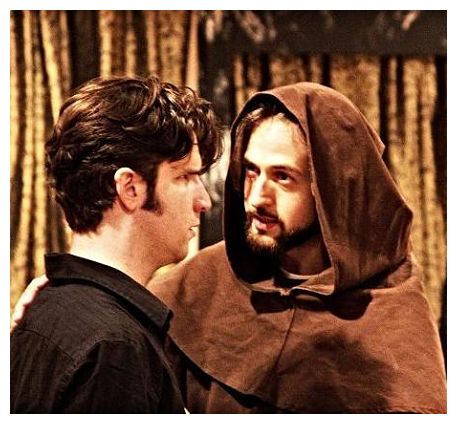

Shakespeare does not resolve those impossible contradictions. He uses a plot device to preserve Isabella's virtue, Claudio's life and the authority of the state. That wily Duke hasn't been absent at all, but rather has been masquerading as Friar Ludovic, haunting convent, prison and city, observing the consequences of his abdication of responsibility. A complicated switch of beds ensues, exposing Angelo's vice and resulting in a final scene full of betrothals.

Measure for Measure was labeled a comedy and by the least stringent of standards -- the happy ending with lots of promised marriages -- it is. But even there, Shakespeare leaves us with unresolved questions. Duke Vincentio steps back into power with no evident resolve to confront the contradictions of law and social behavior that obsessed the flawed Angelo. He happily pulls off the magic trick of revealing that Claudio, reported executed, is in fact alive, then out of the blue announces his intention to wed the demure, caste almost-nun Isabella:

. . . for your lovely sake,

Give me your hand, and say you will be mine,

He is my brother too. But fitter time for that.

Isabella has not a word of reply to this. After his walk on the wild side, this duke of misrule concludes the play by punishing fantastical Lucio for mendacity and summoning all away to the palace to discuss his marriage plans.

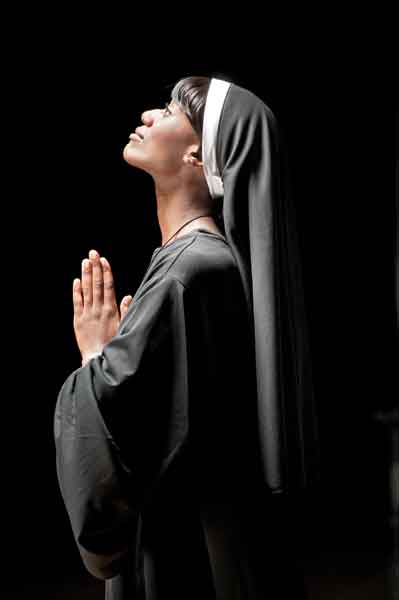

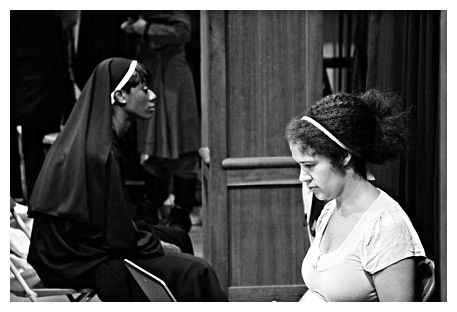

Chad Bradford portrays Duke Vincentio as lightweight and in fact, something of a simpleton. In friar's garb he gets laughs by his airy ignorance of the clerical function -- he can't even make the sign of the cross correctly. There's no air of command about him as Duke and there's no air of sanctity about him as Friar Ludovico. One has the impression that he's wandering around the scene, vaguely interested by what's going on. Brandi Rhome as the novice Isabella, object of the governor's lust, is a lovely slim presence who delivers a one-note performance of tight indignation.

Far more interesting are prisoner and governor. Aidan O'Reilly has a hoarse dignity as the imprisoned Claudio. He shows us the vivid, turning, tightly controlled emotions of hope, incredulity, confusion and despair as Isabella explains the impossible constraints of his situation.

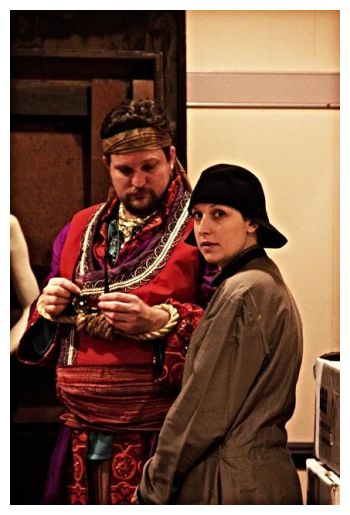

Jake Mahler as the intense and tempted governor Angelo delivers a fierce and believable performance. One hears and sees his devotion to righteousness; one witnesses the power of the evil that twists his virtue to lasciviousness, corruption of the flesh and the injustice of murder by authority. Before the performance and at the interval he reveals himself to be a fine country tenor and musician, as well, and it's easy to imagine him in a mountain gospel quartet lamenting the weakness of the flesh.

More acclaimed by the audience were the shady characters. Rick Blunt, who serves as the troupe's pre-show master of ceremonires, tout and loud friend to all, was a favorite. In the aisle beforehand, a UT staff member congratulated him in advance on his role as Lucio the fantastic ("That's a great role! Everybody loves Lucio!"). In the event, Blunt played Lucio as a fairly serious and concerned libertine. Lucio's downfall is his bragadoccio and yarn-spinning, particularly when he boasts to Friar Ludovico (the Duke in disguise) that he's an initimate of the Duke. Embellishing the story, Lucio puts some slanders on the Duke's own conduct, including unchastity. Lucio gets his comeuppance for spreading those tales, but given this Duke and this staging, one might wonder whether there wasn't some truth in 'em, after all.

The whole cast is articulate, coordinated like clockwork and practiced, thanks to the six months of performing this piece and two more in the repertory of the 'Restless Ecstasy' tour. They deliver a vigorous comedy in Measure for Measure, one that sends you off happy into the evening. That, in a nutshell, is both the upside and the downside of this staging of a text that contains so much more.

The whole cast is articulate, coordinated like clockwork and practiced, thanks to the six months of performing this piece and two more in the repertory of the 'Restless Ecstasy' tour. They deliver a vigorous comedy in Measure for Measure, one that sends you off happy into the evening. That, in a nutshell, is both the upside and the downside of this staging of a text that contains so much more.

EXTRAS

Audience leaflet: Stuff That Happens in the Play

Notes by Director Jim Warren, American Shakespeare Center

List of Cast and Artistic Team

Hits as of 2015 03 01: 1373

Measure for Measure

by William Shakespeare

American Shakespeare Center touring company